The ITM Community: Part I, An Introduction

An MLIS Case Study

It’s Wednesday evening and Steve had just closed his work computer for the day. It was more than an hour past his usual quitting time. It had been quite a week so far. As Steve packed up his bag and headed out of the building, he decided at the last moment to skip the bus and walk over to an Irish pub nearby. Steve had been there a few times before. Usually to watch a sports game, but never on a weekday evening and he hoped it would be quiet. Surely, it’ll be quiet. It’s Tuesday.

As Steve opened the door, he could hear that distinctive Irish music playing inside. As he stepped in and moved towards the bar to get that much-needed drink, he noticed off in the corner of the room a surprising source for the music. Tucked away in that small cozy little corner there were no less than ten musicians playing away on instruments of all types. They were all playing in unison, yet there seems to be no sheet music in sight. Surely, they must be a band. They must practice together all the time.

Steve grabbed his drink from the bar and took a seat near the musicians, entranced by what he saw before him. As he continued to watch his mind filled with questions. Suddenly the struggles of his day had completely left his mind and he felt a strong urge to dance. Who are these people? Do they play here often? Steve noticed they seemed to be taking turns starting tunes. When someone new started a tune everyone else listened to the first part then, as if a light bulb turned on, their faces showed recognition, and they all joined in. Did they not know what was going to be played? If not, how do they know what to play? Have they memorized all this music?

What Steve had stumbled upon is called an Irish session. A curious community of traditional Irish folk musicians who gather in pubs to play music. According to Bates explanation of the various categories of communities an Irish session would classify as an activity-based community (Bates, 2018). The activity is no doubt the playing of music, but it need not be in a pub. In fact, some sessions happen in homes, or in bookstores. On occasion they are even held in parks. What remains constant is the community and activity.

Attempting to define an Irish session can be as difficult as trying to define information itself. In the often-whimsical book Field guide to the Irish music session (Foy, 2009) a session is defined as “…a gathering of Irish traditional musicians for the purpose of celebrating their common interest in the music by playing it together in a relaxed, informal setting, while in the process generally beefing up the mystical cultural mantra that hums along uninterruptedly beneath all manifestations of Irishness worldwide.” Or “…an elaborate excuse for getting out of the house and spending an evening with friends over a few pints of beer” (p.12-13). Both are quite accurate.

The members of this community are as diverse and nuanced as the music itself. Many from the older generations grew up playing this music in Ireland. Another group might be the former classical musicians who use Irish traditional music (ITM) as an escape for the rigidity of orchestral scenes. Another segment of the community might be those who discovered it later in life and were simply curious. The community is filled with doctors, scientists, artists, scholars, even professional musicians may find themselves spending an evening in the pub with their amateur peers. It is a truly egalitarian community where all musicians are equal.

Aside from simply playing music, the Irish session serves as an information ground. Fisher and Fulton describe these locations as “informal, offline, and online, social settings where people experience information – often with complete strangers – while focusing on another activity.” (Fisher et al., 2003, p. 43) This is a very accurate description of an Irish session. In many cases, the session is the sole location where these musicians see each other. Not only do they share news and gossip from their lives and about the community at large, but they also share new music.

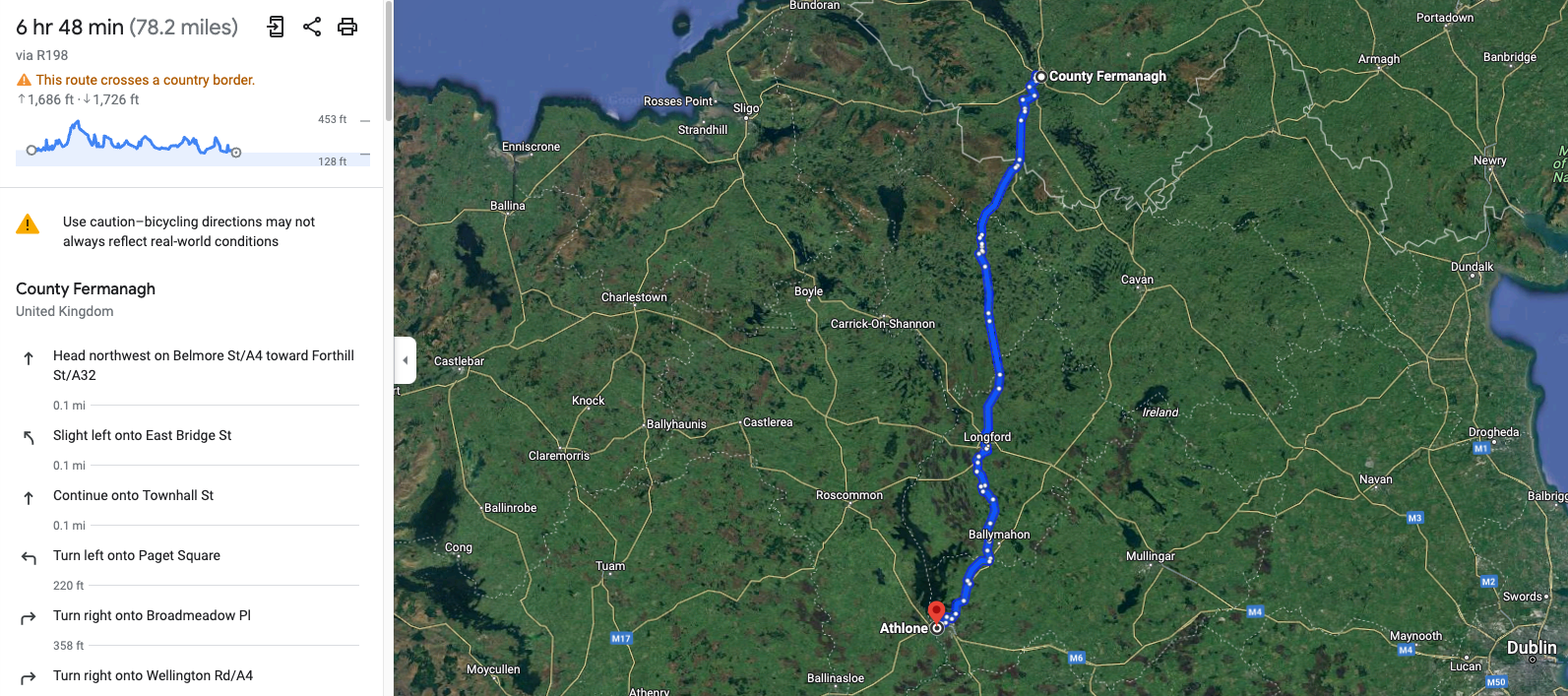

One of the biggest quandaries of Irish musicians is how they go about learning new music. In the book The wheels of the world: Three hundred years of uilleann pipers (Harper, 2015) John McSherry, a prominent piper and founding member of the world famous band Lúnasa, tells of learning the bagpipes in his childhood, and of one man who traveled from Fermanagh to Athlone by bicycle just to learn a tune he had heard about. That’s a near seven-hour bike ride according to Google Maps (Figure 1). If you frequent the sessions with these musicians, you’ll often hear the older generations discussing how they would play old 78’s on loop and slowed down to hear as much of the musical nuance as possible to learn the tune by ear. In fact, the origin of where one might have learned a tune has prompted a very common question, “Where’d you learn that?” As in, who taught it to you? Which recording did you learn it from?

Figure 1. The distance between Fermanagh and Athlone by bicycle. (Google, n.d.)

Today, technology has eased the burden of trying to learn new music and interacting with other musicians. No longer does one need to cycle 80 miles to learn a tune, or even get music lessons. There are numerous websites such as the Online Academy of Irish Music (OAIM) which create communities of practice (Kenny, 2013) that have existed long before Covid. During covid, many ITM musicians turned to Zoom and other streaming formats to conduct sessions. Many of these musicians still use zoom post covid due to their popularity and ability to reach communities that may not have a proper in-person session. This is an excellent example of Fisher’s 3rd tenant of information communities, the capacity to exploit the information qualities of emerging technologies. (Fisher et al., 2003)

Figure 2. The student dashboard for OAIM. Here you can see the many tools for education and community.

For more than a century these musicians have gone out of their way to be a part of this community and learn from each other. The community of Irish musicians exhibits all four aspects of community as outlined by Christen and Levinson’s introduction to the Encyclopedia of community: From the village to the virtual world (Christensen& Levinson, 2003)

Affinity, their shared passion for the music.

Instrumental, their desire to carry on the traditions before them.

Primordial, a strong connection to the Irish culture, from which many of them came if not directly a part of.

Proximate, the very pubs and homes they congregate in.

These qualities also highlight Fisher’s 5th tenant for information communities, the capacity to foster social connectedness. (Hirsh, 2022)

Knowing what we do about these musicians, how they gather, their desires, and passions for music, and how information has been transmitted in the past, we can begin to understand the information needs as outlined in Information services today: An introduction (Hirsh, 2022). Several questions I would like to explore in the ITM information community include the following. How can the information grounds be improved to foster and strengthen the community? What are the threats these communities face? How can we improve the transmission of information and preserve the culture that informs it? What technologies currently exist. What new ones can be used to assist in these endeavors?

References

Christensen, K., & Levinson, D. (2003). Encyclopedia of community: From the village to the virtual world. (Vols. 1-4). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412952583

Fisher, K. E., Unruh, K., & Durrance, J. (2003, October). Information communities: Characteristics gleaned from studies of three online networks. American Society for Information Science and Technology, 40(1), 298-305 https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.1450400137

Foy, B. (2009). Field guide to the Irish music session. Frogchart.

Google. (n.d.). [Fermanagh, Ireland to Athlone, Ireland by bicycle]. Retrieved February 11, 2024, from https://maps.app.goo.gl/MyeCQvYz9yqa5JhB8

Harper, C. (2015). The wheels of the world: 300 years of Irish uilleann pipers. Jawbone.

Hirsh, S. (Ed.). (2022). Information services today : an introduction (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Kenny, A. (2013). The next level: Investigating teaching and learning within an Irish traditional music online community. Research Studies in Music Education, 35(2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X13508349

McDonald, J.D., & Levine-Clark, M. (Eds.). (2018). Information. In Bates, M. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (4th ed., pp. 2347-2360). CRC Press. https://doi-org.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/10.1081/E-ELIS4

Online Academy of Irish Music. (2024, February 11). https://member.oaim.ie/clientarea/dashboard